As America concludes the most turbulent presidential race in recent history, it is important to remember that we are all on the same ship.

Despite fashionable rhetoric, it is not fair to characterize those who do not have the same political philosophy as you as evil demons. Such characterization undermines the humanity of others, discounting their individuality and opening the door to acts of violence. Few things could be more destructive to our collective fate.

Before we proceed, it may be worth it to click here to read my summary of The Righteous Mind by Jonathan Haidt. Great books have a tendency to find their readers at the right time.

A healthy discourse is critical to the functioning of a democracy. A healthy discourse requires honest, respectful, and abundant communication. Your opinion really matters, and so does your neighbor’s, but most importantly so does your political rival’s. Let me explain why.

Plinko!

As frustrating as it may be, humans can rarely do much better than “plinko-ing” through time.

Bear with me.

We can only arrive at the efficient long term equilibrium from the fair and constant battle of ideas and their corresponding policies. This connects to the wisdom of crowds, the “invisible hand“, and spontaneous order. By casting your vote, if not literally then just by your actions, you interact with the system and exert important influence.

This is the competitive advantage of a healthy democracy over any form of top-down rule; our system leverages dynamics that exist in nature to remain adaptive in an incomprehensibly complex world.

I plan to talk about the human Plinko more in the future, but for now think of an idea as the ball and each individual as a peg. The idea (or policy) deterministically navigates through time buffeting against its environment until it settles into its utility equilibrium: either embraced or rejected in aggregate. As the idea interacts with its human environment, it is subtly influenced by that interaction and goes through a process of iterative improvement (or deletion) similar to natural selection.

Law, economy, and culture are emergent properties of the human societies that spawn them. Exerting conscious control over these domains, let’s say as a tyrant forcing a change and stifling resistance, can only last briefly or catastrophically (and often both).

From this perspective, as long as we agree to participate in honorable and respectful discourse everything will sort itself out in time.

Well, of course there’s the problem.

Distrust

Okay, yes, it may be too much to ask for humans to always avoid our natural proclivity toward violence. But there seems to be other factors that are increasing political discord.

America is in a period of historically low trust in its government.

If belief in the system of order is sufficiently undermined, whether by corruption or incompetence, we collectively nudge our plinko ball toward finding a new option. This action comes with costs, and is understandably chaotic. Might this be a source of the political animosity we are seeing today?

Distrust is not inherently a bad thing. It is actually a patriotic thing to be skeptical of our government, what American philosopher Thomas Paine called the necessary evil. One just hopes that it can prove itself more necessary than evil.

In the data collected above we see the trust of the post World War era rapidly degraded during the calamities of the Vietnam war, and deservedly so. This was a period characterized by confirmed government lies (see Pentagon Papers), abuse (see Watergate), and dishonor (no citation needed). We see a spike in 2001 as the country rapidly coalesced in the aftermath of 9/11, but this was squandered in the mismanagement of a long term occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq. Déjà vu.

So the political contention we are seeing today may be a natural response to a dysfunctional system. The individuals are doing their part to find a solution: jockeying ideas and evaluating options. Playing plinko.

Channeling this energy toward the system in order to refine it is a good thing. However, in this period of stress, to direct acrimony against other participants is to lose sight of the goal and potentially damage the process.

Danger Close

Here we are today. Trust is low, animosity is high: conditions feel ripe for upheaval.

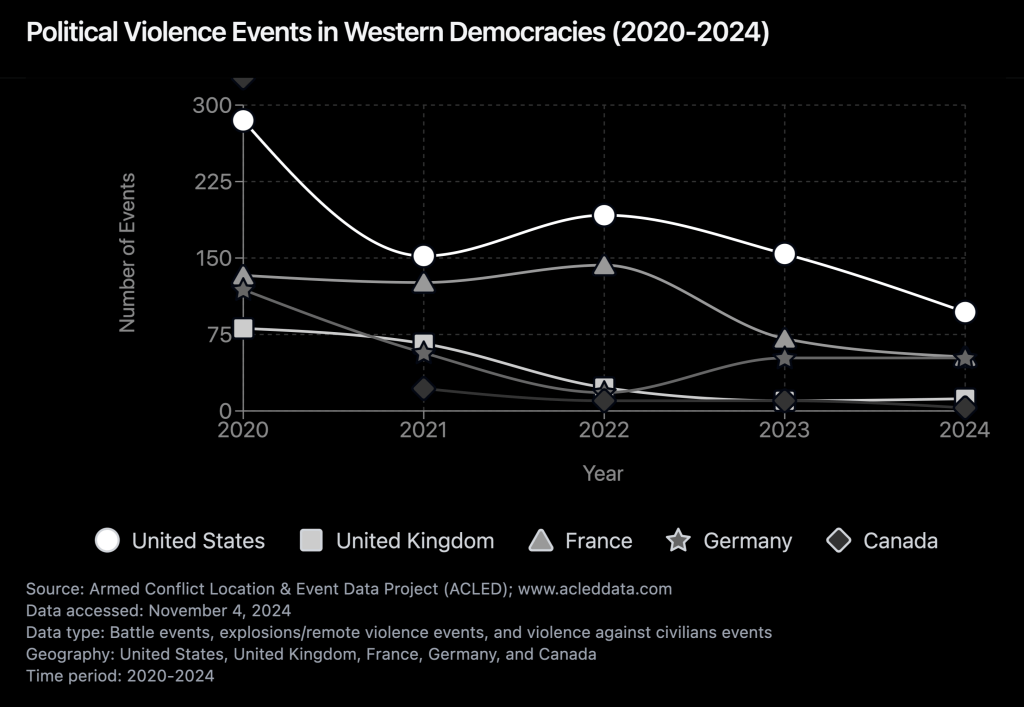

Therefore, it may be surprising that political violence in the West has been declining over the past four years. This data may be skewed by the pandemic, an event which has a historical tendency to increase political instability. Either way, if 2020 was an exceptional period of political stress, maybe our democracy is more robust than it seems.

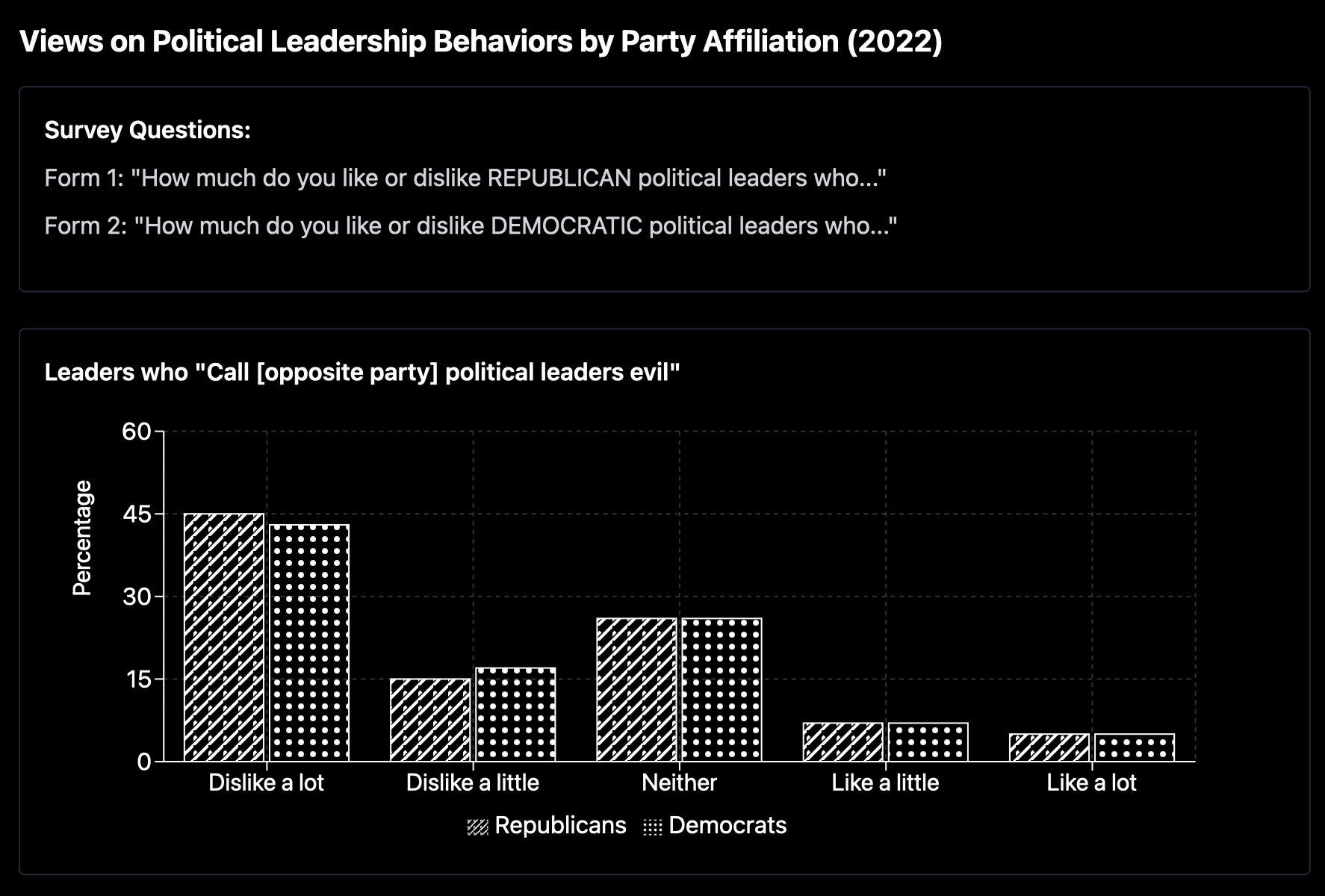

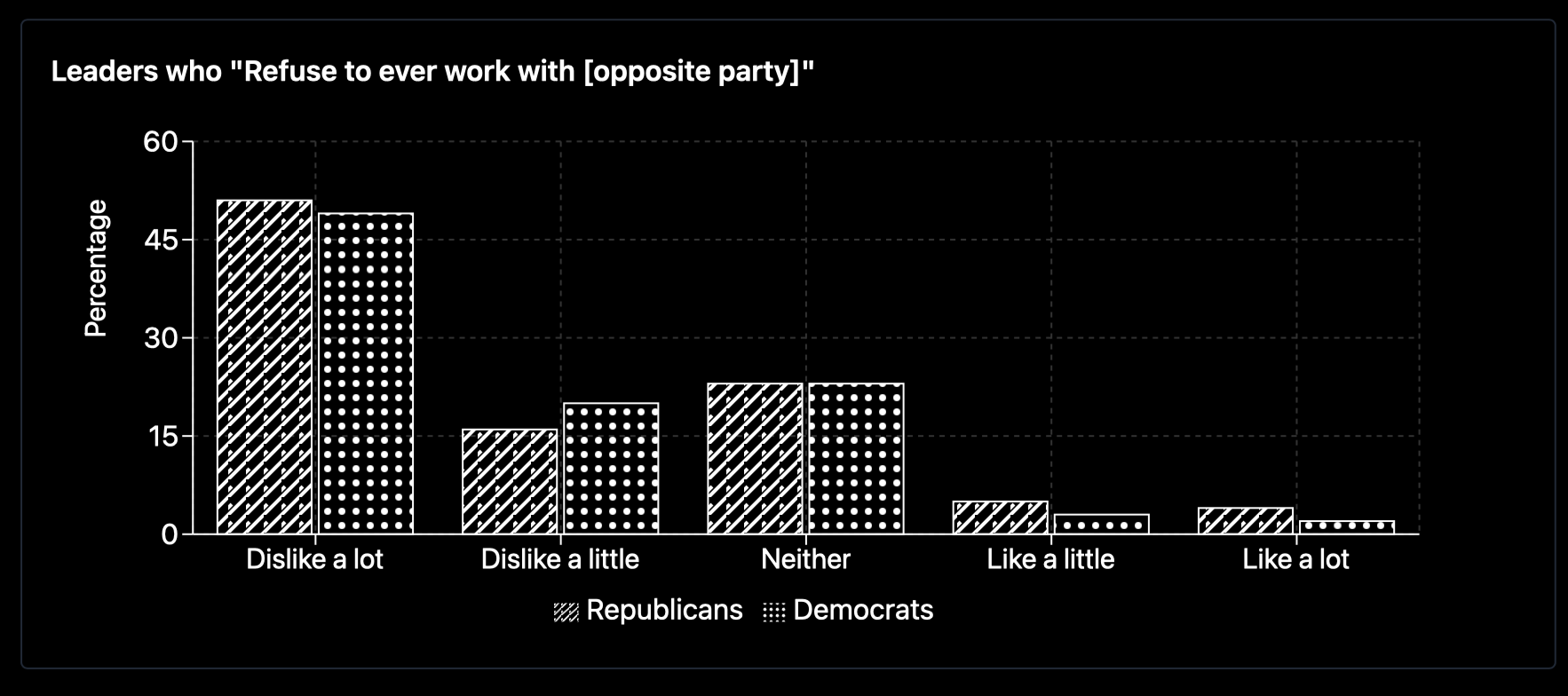

Further, the most vitriolic political anger is concentrated in a minority of partisans. The majority, on both sides of the aisle, appear to be far more reasonable and tolerant of differences.

So America is perhaps more stable and tolerant than it is commonly perceived. This is not so surprising, but it may be problematic. The perception of instability itself can have a causal effect, thereby manifesting conflict that didn’t previously exist. Why does this misperception exist then?

One theory, of many, is that polarizing forces may be inherent to the information age. The communicativeness of people has greatly increased in the past twenty years. Individuals can easily interact with a much larger audience and form widespread communities. This has even spawned an “influencer” class of citizens, who can grow their networks, and therefore their wealth, by producing content that is favored by their platform. Content proliferation tends to favor drama and extremes, because:

- That is what humans actually have an appetite for, over the banal and typical.

- It is easier to group such content into a specific bucket for algorithmic sorting and dispersion.

Then, because humans actually do have more appetite for such content, it creates a positive feedback loop of consumption.

The resulting distortions are becoming increasingly well documented. As it stands, it may continue to radicalize outliers of the population, but I do not think media proliferation (even by nefarious actors) could reach a critical mass alone and destabilize the country. So everything is alright in reality.

Not quite.

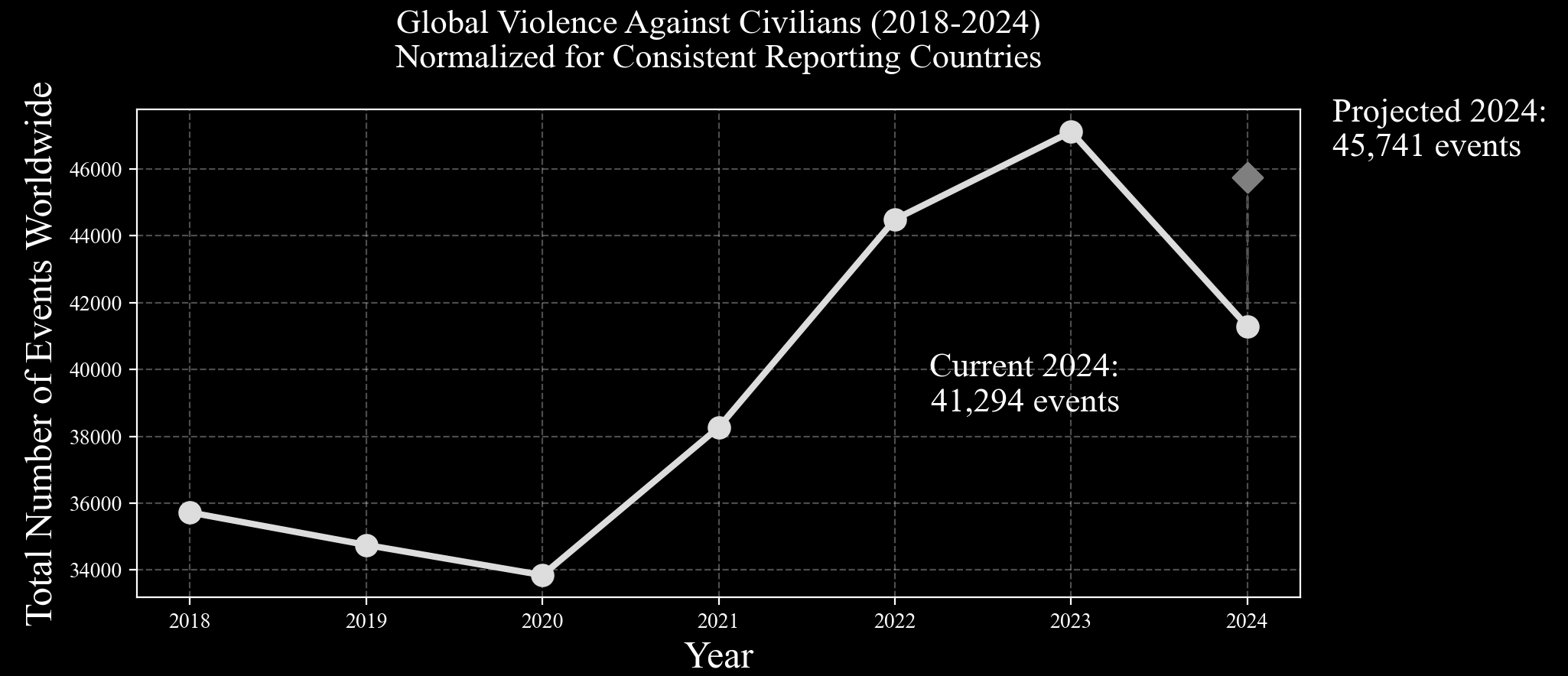

Despite the relative peace America has enjoyed, global violence has been increasing over the past 4 years. Though this year-to-date data shows a slight decline in violence, the ACLED noted that there has been an increase in the number of countries experiencing sustained or increasing conflict. Indeed even countries that are not currently in conflict are posturing to be. So although the instances of violence are down, the potential remains very high.

Volatility begets volatility.

I bring this up because I do not mean to trivialize the gravity of the moment; I believe we are indeed headed for a period of increased geopolitical instability. I believe that it will require our utmost vigilance to navigate this era successfully. However, much more so, I believe it will require our cooperation.

Conclusion

I am an American skeptic, and an American exceptionalist. The United States is a special place in the world, not because of the federal regimes that have led it but because of the people who have composed it. The American Abraham Lincoln said,

“At what point then is the approach of danger to be expected? I answer, if it ever reach us, it must spring up amongst us. It cannot come from abroad. If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen, we must live through all time, or die by suicide.”

Too often recently I have heard casual talk of civil war – God forbid it comes to that again. If it may, and in a millennium it may, one could only hope it be for the preservation of individual freedom and liberty. It is the only way we can plinko our way to a happy future for all.

There is no greater cause.

We are all on the same ship, and it can only navigate through rough waters if we each plunge our oars in unison. It will require all hands on deck.

The Economist just produced an essay titled “The anti-politics eating the west”- funny how this idea has itself become emergent recently. The essay concludes true to their stylistic form:

The idea that the vote in America on November 5th could determine the path of history is the sort of grandiose claim you would expect from partisans trying to stir up their base. This time it might just be true.

It’s nice to end an essay with a dramatic line, but part of me disagrees with the sentiment. The election will indeed determine the path of history, as they all do.

Though perhaps not as much as you.